The Stanford Prison Experiment was a controversial psychological study conducted in 1971 by Dr. Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University. The purpose of the experiment was to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power, focusing on the struggle between prisoners and prison officers.

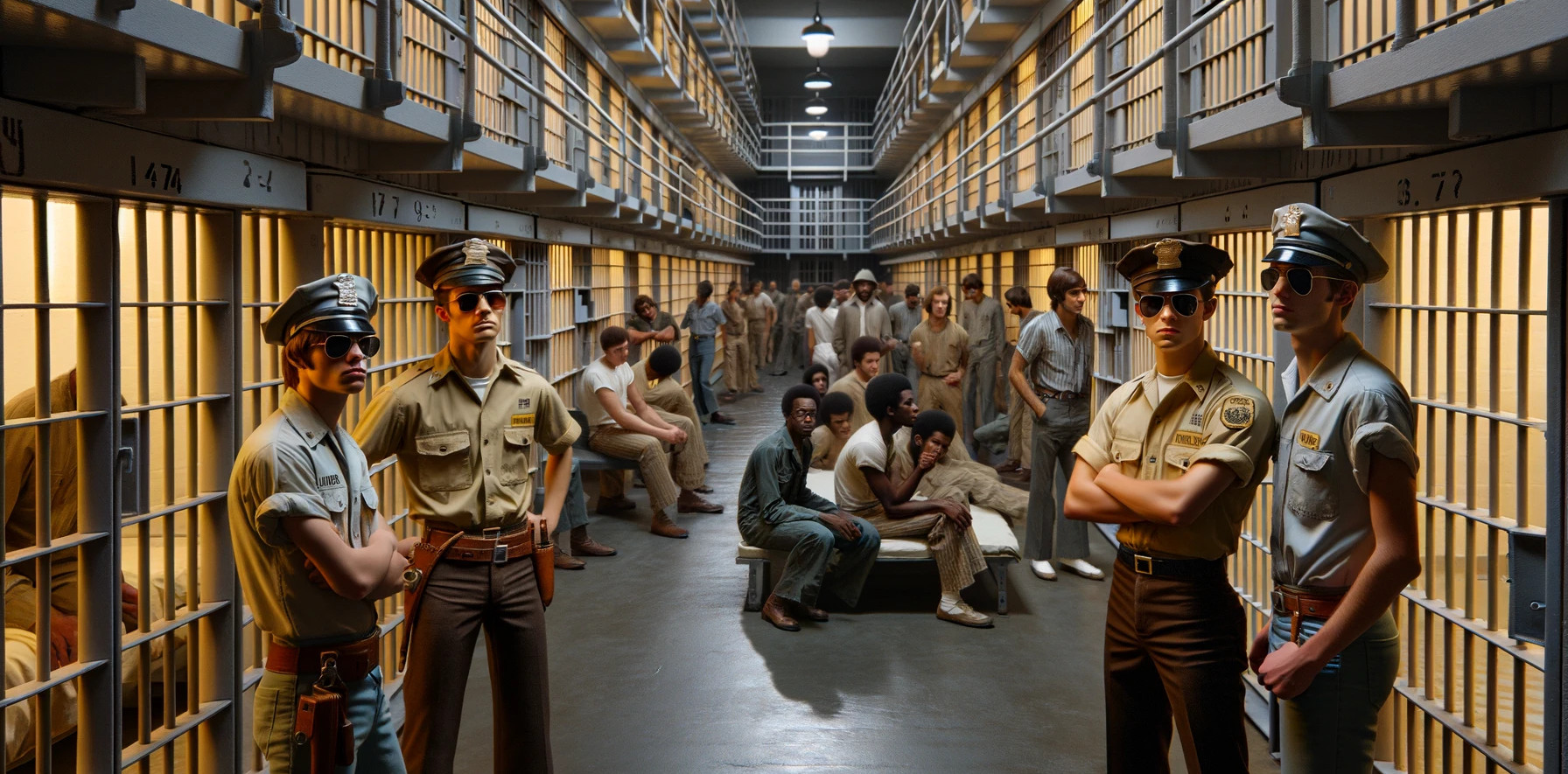

In the experiment, 24 male college students were selected and randomly assigned to either the role of a prisoner or a guard. The study was conducted in a simulated prison environment set up in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. The participants were given uniforms and props (such as sunglasses for the guards) to enhance their roles.

The experiment quickly spiralled out of control. The guards, who were given authority and minimal guidelines, began to exhibit abusive and authoritarian behaviour. The prisoners, subjected to harsh treatment, experienced severe stress and emotional trauma. This behaviour was not anticipated to the extent it occurred, and it raised ethical questions about the methodology.

The experiment was initially planned to last two weeks but was terminated after just six days due to the extreme emotional distress exhibited by the participants. The Stanford Prison Experiment has since become a classic example in psychology, demonstrating the influence of situational factors on behaviour and the potential for people to conform to roles, especially in hierarchical settings like prisons. However, it has also been criticized for ethical concerns and questions about scientific rigour, including the possibility of participant behaviour being influenced by expectations from the experimental setup.

In politics

The Stanford Prison Experiment provides a compelling framework for understanding the transformation that can occur when university academics, typically steeped in a world of theoretical and intellectual pursuits, transition into the realm of politics, a domain often marked by tangible and perceived power dynamics. This shift mirrors the transition observed in the experiment, where ordinary individuals suddenly found themselves in roles imbued with authority and control. Just as the ‘guards’ in the experiment adopted authoritarian behaviours far removed from their everyday personas, academics entering politics can similarly find themselves adapting, sometimes unconsciously, to the power structures inherent in their new roles. This adaptation can lead to significant changes in behaviour and decision-making processes, influenced by the new environment’s demands, expectations, and pressures. The Stanford Prison Experiment serves as a reminder of the profound impact that situational power can have on individuals, highlighting the psychological metamorphosis that may occur when academics leave the theoretical confines of the university for the pragmatic and power-laden world of politics.

Implications

The Stanford Prison Experiment vividly illustrates the perils of allocating power to individuals who are not only immature, but also lack real-world experience and understanding. In the experiment, college students, with their limited life experiences and undeveloped maturity, were abruptly placed in positions of authority (as guards) or subjugation (as prisoners). The rapid descent into authoritarian and abusive behaviour by the ‘guards’ underscores the dangers of entrusting power to those who are ill-prepared to handle its responsibilities and consequences. Their inability to navigate the complex ethical and interpersonal challenges that come with authority led to a breakdown of order and the infliction of psychological harm. This scenario mirrors the potential societal risks when power is vested in individuals who lack the maturity and real-world wisdom to wield it judiciously. It highlights the necessity for a deep understanding of human nature, ethics, and responsibility in leadership roles, and serves as a cautionary tale about the disastrous implications for society when power is allocated without considering the individual’s readiness and capability to manage it responsibly.