The Olmecs were a pre-Columbian civilisation known for being among the first complex societies to develop in what is now Mexico, around 1400-400 BCE. Often considered the mother culture of Mesoamerica, the Olmecs laid many of the foundational elements for the civilisations that followed. They inhabited the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. The Olmecs are particularly renowned for their colossal head sculptures, intricate jade figurines, and their contributions to early writing systems and calendar-making. Their society was complex, with a rich mythology, advanced agricultural practices, and significant achievements in architecture and urban planning. The Olmec civilisation’s influence extended far beyond their heartland, impacting the cultural development of the region through trade networks and cultural diffusion.

Forerunners of the Mayans and the Aztecs

The Olmecs are often regarded as the forerunners of later Mesoamerican civilizations, including the Maya and the Aztecs. Their civilisation provided foundational cultural, religious, and technological advancements that influenced the subsequent development of these and other Mesoamerican societies. They developed early forms of writing and the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar, which were later adopted and adapted by the Maya. Their religious symbols and deities, particularly the were-jaguar motif, are seen in the iconography of later cultures. Moreover, their innovations in agriculture, city planning, and architecture set standards that were emulated by succeeding civilisations. The Olmecs’ extensive trade networks helped spread their cultural and technological innovations across the region, aiding in the cohesion and development of Mesoamerica’s complex societies. This deep influence establishes the Olmecs not just as a precursor but as a foundational culture upon which later civilisations built their own unique advancements.

Their political system

The specific details of the Olmec political system are not fully understood, mainly due to the limited written records from the period. However, archaeological evidence, including monumental architecture, sophisticated urban planning, and artefacts, suggests that they had a complex society with hierarchical social structures. This evidence points towards some form of centralised leadership or governance. Here are some insights into their likely political organisation…

Elite Leadership:

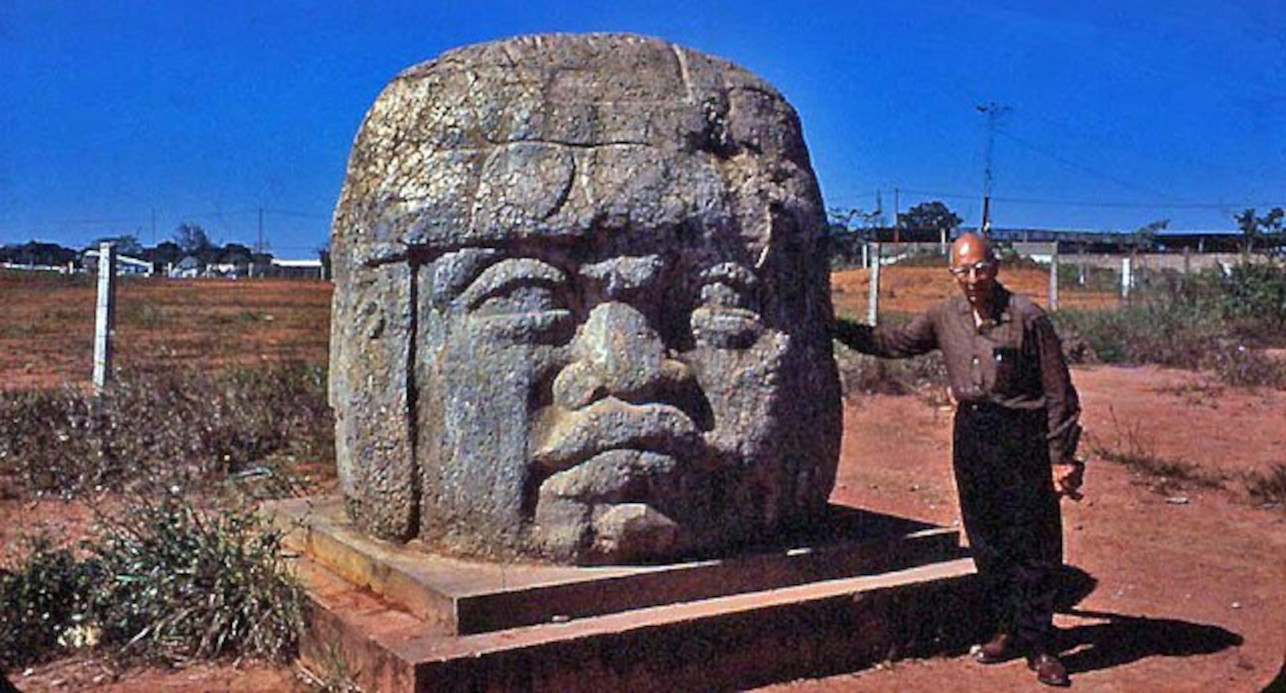

The Olmecs probably had a ruling elite, possibly consisting of religious leaders, chieftains, or kings. The construction of large ceremonial centres, colossal head sculptures believed to represent rulers, and elaborate burial sites indicate a society with significant social stratification and a powerful leadership class.

Religious Influence:

Religion likely played a crucial role in Olmec society, with the ruling elite possibly doubling as religious leaders. This dual role could have legitimised their authority through divine sanction or connection to the gods, which was a common feature in later Mesoamerican civilisations.

Centralised Control:

The scale of construction projects, such as pyramids, plazas, and monumental sculptures, implies a form of governance capable of mobilising and organising large groups of people for communal projects. This suggests some level of bureaucratic or administrative control to manage resources, labour, and ceremonies.

City-States or Chiefdoms:

Some scholars propose that the Olmec society was organised into city-states or chiefdoms, each with its own leader or ruling family. These centres, like San Lorenzo and La Venta, could have acted as political, religious, and economic hubs, with a central authority governing the surrounding areas.

Network of Influence:

The widespread distribution of Olmec-style artefacts and iconography suggests they had influence over a broad region, possibly through a network of alliances, tribute systems, or trade relationships with neighbouring groups

Their religion

The Olmec civilisation, had a complex pantheon and religious beliefs, though specific names of their gods are not as well-documented as those of subsequent civilisations like the Maya and Aztecs. Here are some key aspects of Olmec religious practices and deities…

The Were-Jaguar:

One of the most iconic and widely recognised Olmec religious symbols is the were-jaguar, a figure that combines human and jaguar features. It’s believed to represent a deity or a set of supernatural entities related to fertility, agriculture, and possibly rain. The were-jaguar motif appears in various forms of Olmec art, including sculpture, figurines, and carvings.

The Dragon:

Another important mythical creature in Olmec religion is often referred to as the Olmec Dragon. It appears to combine features of several animals besides the dragon, such as a crocodile and a bird, and is thought to represent the earth or fertility.

Rain and Corn Deities:

While specific names are not known, evidence suggests the Olmecs worshipped deities associated with rain and maize (corn), which were critical for their agricultural society. These deities would later evolve in the pantheons of successor civilisations into more recognisable forms, such as the Maya god Chac or the Aztec Tlaloc.

The Maize God:

Although more directly associated with later cultures, some evidence suggests the Olmecs might have also revered a form of a maize god, given the importance of corn in their diet and economy. This deity is typically represented as a young man associated with growth, renewal, and fertility.

Celestial and Underworld Deities:

The Olmecs likely believed in a layered universe with celestial realms, the earth, and the underworld. Deities associated with these realms would have played significant roles in their cosmology and religious practices.

Human sacrifice

There is evidence suggesting that the Olmecs practised human sacrifice, although the extent and nature of these rituals are not as well documented or understood as those of later Mesoamerican civilisations like the Aztecs and Maya. Archaeological findings, including depictions in art and the discovery of remains, indicate that human sacrifice was part of Olmec religious ceremonies.

Artistic Depictions:

Some Olmec sculptures and carvings depict scenes that have been interpreted by scholars as indicative of human sacrifice. These include images of figures in postures or contexts that suggest ritualistic killing or offering.

Burial Sites and Remains:

Archaeological excavations at Olmec sites have uncovered remains and burial sites that some researchers interpret as evidence of sacrificial practices. In some cases, the manner in which the bodies were placed or the artefacts found with them suggests they were offerings to deities or part of ritual ceremonies.

Ceremonial Centres:

The layout and artefacts found within Olmec ceremonial centres, such as La Venta, suggest that these sites were used for complex religious rituals that could have included sacrifices. Altars and other ceremonial objects indicate a deep spiritual significance to their practices, which likely involved offerings to the gods.

Olmec centres

The Olmec civilisation is known for its significant urban centres, which, while not cities in the modern sense, were extensive and complex for their time. These centres served as focal points for religious, political, and economic activities. The most well-known Olmec sites include San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes, each of which provides insight into the scale and sophistication of Olmec urban planning and architecture.

San Lorenzo

San Lorenzo is considered one of the earliest major Olmec urban centers, flourishing from around 1400 to 900 BCE. At its peak, San Lorenzo was a sprawling complex that included monumental stone sculptures, such as the colossal heads, extensive terracing for agriculture, and sophisticated water management systems. The site covered approximately 700 hectares (around 1730 acres), with the core area featuring elite residences and ceremonial structures.

La Venta

La Venta is another critical Olmec site, which became prominent from around 900 to 400 BCE, after the decline of San Lorenzo. It is known for its unique earthen pyramid, complex mounds, monumental stone sculptures, and altars. The site covers over 200 hectares (around 500 acres), with a complex layout that includes a central ceremonial area aligned with astronomical features. La Venta’s Great Pyramid is one of the earliest known Mesoamerican pyramids, suggesting a significant degree of social organisation and labor mobilization.

Tres Zapotes

Tres Zapotes is notable for its longevity, with Olmec occupation dating from around 1000 BCE and influences persisting well into the Classic period of Mesoamerican history. The site features monumental sculptures, including one of the colossal heads, and evidence of sophisticated urban planning. Tres Zapotes covered a large area, though the full extent of its size during the Olmec period is difficult to determine due to later cultural overlays.

Urban Features and Significance

The urban centres of the Olmec civilisation were not large cities by today’s standards, but they were significant for their time. They featured:

- Monumental Architecture:

Including pyramids, mounds, plazas, and monumental stone sculptures. - Sophisticated Planning:

Evidenced by the layout of ceremonial centres, residential areas, and infrastructure such as drainage systems. - Social Stratification:

Indicated by the differentiation in housing and burial practices, with elites likely residing in more complex and centrally located structures. - Economic and Political Centres:

These sites likely served as hubs for trade, religious ceremonies, and political governance, facilitating the Olmecs’ influence in the region.

The scale and sophistication of Olmec urban centres reflect a highly organised society capable of mobilising resources and labour for large-scale construction projects, indicating advanced social, political, and religious systems for their time.