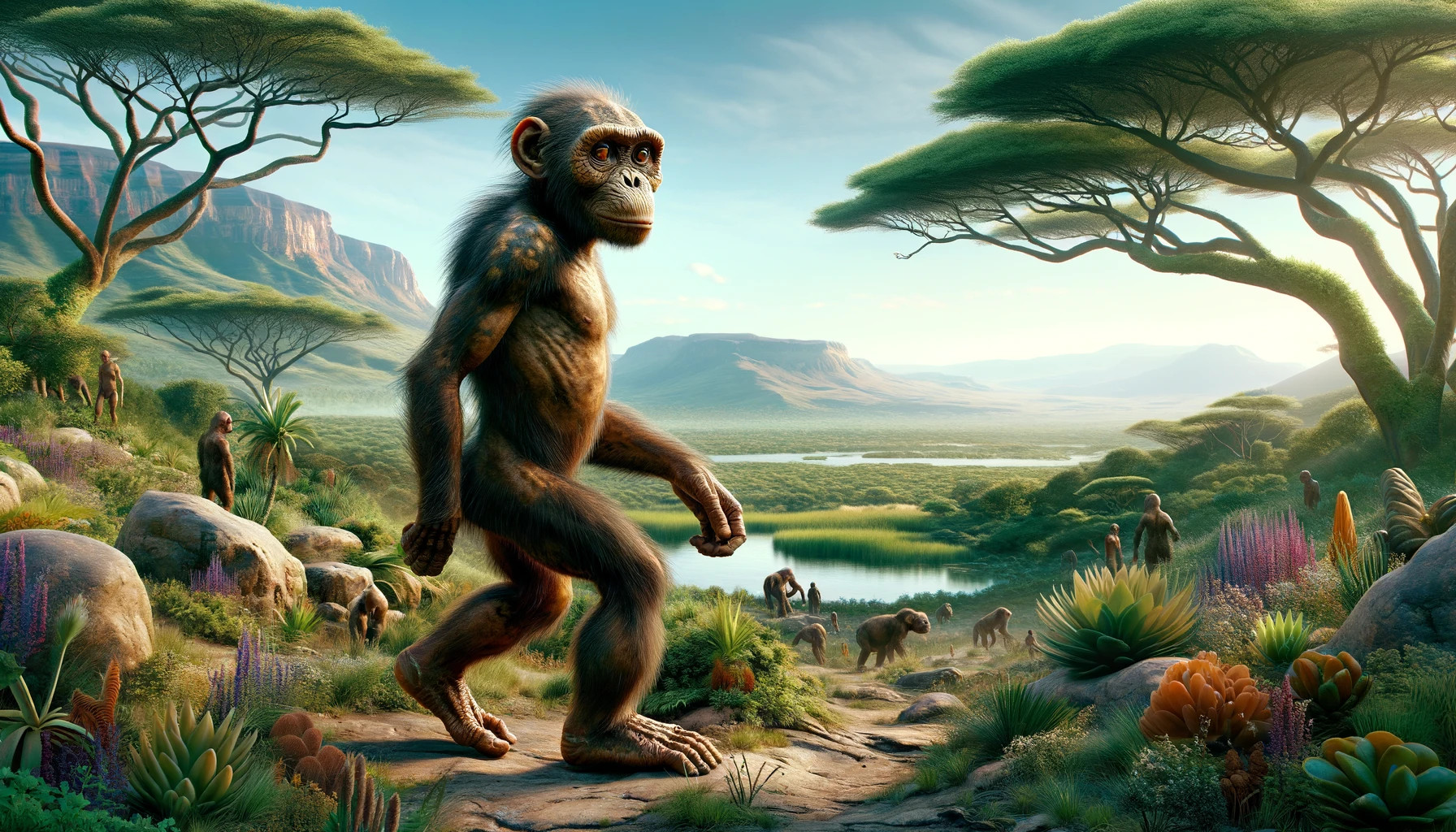

According to the scientific community, the first ever evidence of humanity, or more specifically, of hominins (the group that includes modern humans, our immediate ancestors, and other extinct relatives), dates back to around 6 to 7 million years ago, (you’d think science could be more accurate than this, a million years is a long time). This evidence comes from a combination of fossil finds and archaeological discoveries. Here are some key points:

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis:

Dating back to about 6-7 million years ago, this species is one of the oldest known human ancestors. Its fossil remains, discovered in Chad, Africa, include a nearly complete cranium known as “Toumaï.” - Orrorin tugenensis:

Discovered in Kenya, these remains are about 6 million years old. They include important leg bones, suggesting bipedalism (walking on two legs), a key trait of human evolution. - Ardipithecus ramidus:

Dating back to about 4.4 million years ago, this species was found in Ethiopia. It provides significant insights into early hominins’ physical characteristics and environment. - Australopithecus:

A well-known genus that includes several species like Australopithecus afarensis (famous for the “Lucy” skeleton), these hominins lived between 2 and 4 million years ago. They show clear evidence of bipedalism and were found in various locations in East Africa. - Stone Tools:

The earliest known stone tools, which indicate the beginning of technology and thus a significant step in human evolution, date back to about 2.6 million years ago. These were found in Gona, Ethiopia, and are attributed to the early human species, possibly Homo habilis. - Homo habilis and Homo erectus:

These species, existing between 1.5 to 2 million years ago, are among the earliest members of the genus Homo. They show advancements in brain size and tool-making capabilities. - Genetic Evidence:

Alongside fossil records, genetic studies on modern humans and our closest relatives (like Neanderthals and Denisovans) provide insights into our evolutionary history, dating back hundreds of thousands of years.

These discoveries, although tenuous, collectively provide our current picture of human evolution, showing a gradual development of characteristics that define modern humans, such as larger brain sizes, bipedalism, and tool use.

New scientific discoveries, especially those that challenge established theories or understanding, often face skepticism and scrutiny within the scientific community. This caution stems from both a commitment to rigorous standards of evidence and the reluctance of individuals to change their understanding.. Historically, groundbreaking findings have frequently been met with resistance, as they imply a need to revise or even overturn long-held beliefs. For instance, the initial reception to the theory of plate tectonics or the idea of heliocentrism in astronomy was lukewarm at best. Such reluctance is partly due to the inherent conservative nature of scientific practice, which prioritizes empirical evidence and repeatability. Scientists, being cautious by nature and training, typically require extensive validation and replication of results before accepting new hypotheses.